Stage: communicatie & sociale media

13 Maa 2024

wo 14 sep 2022

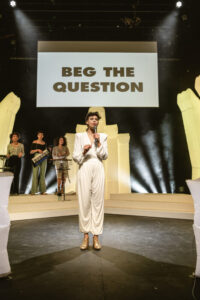

Brazilian-Belgian performer, storyteller, and writer Luanda Casella has been making theatre in Belgium for 16 years and this year her humorous performance KillJoy Quiz appears as part of Het TheaterFestival. To recognise the violence in the world and to fight it with the right language and attitude, she uses the format of a TV quiz show. At the end of the quiz, the title of ‘Best KillJoy’ goes to the contestant who scores the most KillJoy points in a wide range of categories. So, who will be the Best KillJoy? But most importantly, what is the meaning of winning this quiz?

Hazel Lam and Rojda Karakus

© Michiel Devijver

Dressed in smart casual black, Luanda walks into the theatre with enormous charisma and untamed candidness. ‘Please, call me Lua, I feel more comfortable with it.’ Her performance KillJoy Quiz has all the razzle-dazzle a TV quiz needs to have: a 3-piece a capella band, glitter, fast-paced humour, ridiculous decor… We have some questions for Lua, who plays the assertive and enchanting hostess in her show.

Have you enjoyed playing this show so far? It has been more than a year old already. How are things going so far?

Lua(nda) Casella: ‘KillJoy Quiz is a show that we have a lot of fun with. It is a delightful piece for me. I feel that we can really connect with people.’

You are breaking away from tradition. Where do you think KillJoy Quiz sits within the range of your oeuvre?

‘It is true that my work is not traditional storytelling. I am always searching for ways of writing and putting myself in a position where I write differently. So, it is very experimental at that level. We are using popular formats as structures and that is a way I have found to address the public and to surprise myself. I wanted to make a show about the political climate in 2016. Using popular formats breaks the fourth wall as the fiction is on a meta-level. You’re not seeing a quiz, you’re seeing the representation of a quiz.

It’s not just fiction, it is also about participation. I think it is always going back to us as readers because we have a play about language. I always see people interacting with my piece as readers, creating meaning with us. I ask certain questions to the public but that is not the biggest interaction. The biggest interaction is when they are playing the game with the participants.’

What was the most surprising interaction with the audience you’ve had so far?

‘That they love it so much! (laughs) But once there was a man who was angry. I asked him in the show if he had had an abortion. The idea behind it was to open the question of abortion to not only women because there is also a father involved. It was a provocation. He was really upset, and I think this was one surprising moment. But I expected it because I did it on purpose. I really like it when these things happen. It touches people in different ways. It wasn’t meant to be aggressive but he probably took it that way. It then created a bigger meaning for everyone else. When someone gets offended, then he is clearly affirming his patriarchal privileges.’

And he becomes the actor within this play.

‘Indeed!’

The title KillJoy Quiz is a reference to the scholar Sara Ahmed’s KillJoy Manifesto. Were there any other scholars who inspired you during the making process?

‘Many. I was extremely inspired by Saidiya Hartman who wrote Wayward Lives. The idea of speculation is strong in her works. For example, she works in archives and calls it “critical fabulation”. She goes back to tell the story of young black women in the South of the US when they became free from slavery and went North to start new lives in cities like Philadelphia and New York. So it was a story about the first movements of young girls and the sexual revolution they were going through. She demystifies the stigmas that were placed on black women. They were imprisoned by perversity or whatever people were calling them. They exchanged letters. Hartman reconstructs and fabricates what they were telling their mothers and their sisters; what kind of family arrangement they had in poverty. She creates a beautiful picture through which she rescues them from this position of promiscuity and simply victims of slavery.

Another one is Octavia Butler. She has influenced me for my third piece with NTGent, Ferox Tempus. It is more about speculation for the future. Where is the future going?

I like Audre Lorde, I read her a lot. She is funny as well. Ursula Le Guin has inspired me, and she is also a speculative fiction writer.

For KillJoy Quiz, I read a lot about the topics specifically. I read about climate and toxic masculinity in the arts. I surfed a lot on the internet for pearls like Twitter, Facebook, and Reddit. All these chat boxes of poor discussions on language contribute to the topic of polarisation.’

This show is also about the manipulative power of language. When did you realise this topic is something that you want to turn into a play, something you want to address in this, dare we say, ‘post-truth’ society?

‘I think a post-truth society is where we are and that’s what we’re addressing in this world. In my work, I use the idea of language through rhetoric, which is what I studied as well. I studied it in art but it’s also the backbone of everywhere I go. It has always fascinated me how characters in real life become media manipulators, politicians or pseudoscientists. There is always something that binds all these characters together which is the ability to convince people to do things. This ability and charisma in literature has a name for it: the ‘unreliable narrator’. It is a kind of narrator that manipulates people, and my father is one of them. (laughs) My father is a con artist and he manipulates people with language. That is why I am fascinated with this power. This kind of charisma can be harmful as it makes you blind and completely absorbed.

I’m always interested in ambivalence. The state of when you are listening to something, but you are not sure at the same time. You are responsible for believing it or not. Training your capacity to recognise what you believe in or not is what critical thinking is about. In the end, there is no aim in my work, because I don’t believe in doing things for a purpose, but this theme is ever underlying my work. Then when you think about it, the popular formats are also unreliable. You’re not seeing a real quiz, it is a scripted quiz, and that puts you again in the position of deciding things. I want to see what kind of decisions the audience will make to go on with what they are seeing.’

On social media, you posted this quote: ‘What theatre does is to create a common moment for critical thinking…’ Could you explain this?

‘It was from another interview in Brussels. It is horrible for me to say but I don’t like going to the theatre so much. I sometimes have the feeling that I am trapped and I am not having this common experience. I am mostly only touched by things that have a certain humour and irony. For me, the state of irony and the ambivalence we’ve talked about, and the questionable reality are what make critical thinking possible. I do theatre because I like the moment of presence. Also, it is because I am anxious, otherwise I would just write.’

This is very exciting because hearing your emotions drives you to make art. Not any other art, but performing arts.

‘It’s not a solution to my anxiety. My anxiety is not healing through doing these things I am doing now. It’s more like the fact that my anxiety exists, so I live with it. I can write the script and another person acts it out. But when I create something, I know how I want those words to be delivered. That’s why I did many solos many times. So perhaps the big challenge for me would be to write a novel. That would be my dream but I don’t know if I am ready or have the calmness of writing a novel. But more and more I am hungry for it because I feel frustrated by the timeframe of the one or two hours that we have in a theatre. However, I love being in that building, because whatever is happening to my life, whether dying of a broken heart or being extremely excited, the one hour I’m in a theatre goes by in the blink of an eye. For me, being on stage is like a moment of peace. And also, nothing can go wrong in the play. It’s a rehearsed moment of life. Even if it does go wrong we create a sisterhood in the play and we get to the end.’

How do you feel about using English as a lingua franca? Is it a straightforward decision or questionable and have you struggled with it as a language to deliver your art?

‘I can say something about language in general. I have become more comfortable in Dutch but still, I don’t feel myself in Dutch. The construction in Dutch is very indirect. My first language is a Latin language and the verb order and grammatical structure are very different. That is why I felt like an alien at the beginning. Nowadays, I can speak Dutch more and more. I don’t know if I would connect more with the Flemish audience if I spoke Dutch. I don’t know if I would lose the flair of being a foreigner that sometimes plays into the charisma that I try to create for this unreliable character. If you want to deceive someone, you need them to like you. Otherwise, they’re gone. So there is a very precise manipulation of language that goes through being comfortable with the language.

When you talk about linguistic justice, I understand people who want to do things in many languages, because certain things you cannot say in other languages. I feel grateful that English doesn’t have gender for example. I have lost touch with Portuguese now because the masculine form often prevails. It is an interesting thing to look at this specific moment of our history where any kind of change and resistance goes through language. Whatever we want to achieve, for the good or the bad, it always happens through language. We cannot disassociate with language.’

The performance contains some intertextual references. There is a possibility that the people who do not understand the joke would feel excluded. Have you received any feedback from your audience about this?

‘People think it is about politics, but it’s not. It is about reading. I tried to put in as many text forms and discourses as possible. There are quotes from articles, documents from chat boxes, and poems from pieces of prose, and they are performed in different ways.

I want people to be immersed in the atmosphere of reading. It’s not about reading the news and being critical about it. People see women of colour and they would assume their work is about political correctness. Let them think what they want, but I think my biggest proposal is: can they first imagine all of us as readers? That’s my biggest provocation. Can you imagine six women of colour as readers? Period. Not as feminists. Of course, we are feminists, we all are, we cannot be anything but be feminists today.

To go back to the people feeling excluded – it’s ok! I want to make a show where some people can understand it on the most superficial level, as a quiz is due to the popular format. People can “enter” the show because it’s accessible. Especially when people laugh, they become more open. There are many tricks in storytelling that I consciously use in composing to have these effects. And it’s also my conscious choice that some people get it and some don’t. Because for those who get it is the most beautiful thing. The pleasure of irony is the fact that many people didn’t get it. It is part of irony. It’s this blink of the two or three seconds before the joke sinks. There are parts in the show where no one laughs, and then there can be one poor person who goes: ‘Aha!’ At that moment, me and that person are sharing this specific pleasure. I find it thrilling. For me, that’s enough. If others don’t get it, they would get something else. There is something for everyone.’

Some of your works have a stronger political tone and some to a lesser degree. Some people claim that there is an inherent relation between arts and politics. There is a kind of activism in art making. To what extent do your works sit on this spectrum?

‘That’s a very good question. I can think of a few things. One is, of course, that my work is political, but it is political in a sense like this interview with Nina Simone where she says: “How can you be an artist and not reflect on your times?” It is impossible. Everything is political. What she meant in that context is grounded in the civil rights movement. Even though she was an activist, the level of aesthetics that she put in her art is so much bigger than its political messages. It is political but we cannot forget the aesthetic experience. KillJoy Quiz is not a show about politics, but the political messages are there. The choices we make when we wake up are all political. But there is a difference between arts and activist arts. I think we should just differentiate between good and bad art. Whether a piece is activist art or not, it’s just because the aesthetic experience is changing the hearts of people – that would be the activist elements, but not because there are banners with for example ‘Black Lives Matter’ written on them.

You’d think my show is about politics but it is actually about speculation. The quiz is there for you to see a world in which we could envision change. I am always interested in multiple layers of a story where there are parallel happenings. So this show is not about who begins, who ends, or who wins. It’s about competition and things that are already in our heads. Of course, it’s political and it’s on purpose. But I am not here to educate anyone. My motivation is to make a committed work about the pathetic state of polarisation in which we live.’